VIRUS CULTURE

Fear of the Virus replaces fear of the Bomb as the mass American Nightmare

“From the point of view of the virus, we humans are an enormous pile of meat. Viruses don't care about us . . . that we're intelligent. A virus is like Jaws in a test tube. ” - Richard Preston, The Hot Zone

“Few threats have the capability of killing so many so fast. For years we lived under the fear of nuclear winter annihilating the human race. Now there is a similar threat from biology. ”-- Robin Cook, Vector

“The Bomb, so long awaited, is gone. In its place came these plagues, the slowest of cataclysms. ”

-- William Gibson, Virtual Light

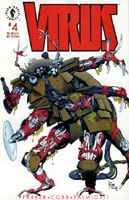

Just as atomic anxiety infused Cold War-era pop culture, virus anxiety -- in the form of plagues, epidemics, parasites and microbe-caused mutations -- permeates current pop culture: the virulent black oil virus in The X-Files, the ghastly Ebola epidemic in Outbreak, the mutated monstrosities in the comic-book/movie Virus and the playstation games Parasite Eve and Syphon Filter.

Just as atomic anxiety infused Cold War-era pop culture, virus anxiety -- in the form of plagues, epidemics, parasites and microbe-caused mutations -- permeates current pop culture: the virulent black oil virus in The X-Files, the ghastly Ebola epidemic in Outbreak, the mutated monstrosities in the comic-book/movie Virus and the playstation games Parasite Eve and Syphon Filter.

On the literary front, there is the post-plague horror of Stephen King's The Stand and Connie Willis' Doomsday Book, the biological hellhole in Dean Koontz's Seize the Night, the anthrax bio-terrorism in Robin Cook's Vector, the thinking microbes in Greg Bear's Blood Music, the hostile computer virus in Philip Kerr's The Second Angel and even a board game called Infection. A new balance of horror has emerged: virus paranoia dominates bomb paranoia as our paramount cultural dread.

On the literary front, there is the post-plague horror of Stephen King's The Stand and Connie Willis' Doomsday Book, the biological hellhole in Dean Koontz's Seize the Night, the anthrax bio-terrorism in Robin Cook's Vector, the thinking microbes in Greg Bear's Blood Music, the hostile computer virus in Philip Kerr's The Second Angel and even a board game called Infection. A new balance of horror has emerged: virus paranoia dominates bomb paranoia as our paramount cultural dread.

Inspiring this cultural anxiety are real fears: the AIDS virus, germ warfare, biological terrorism, the U.S. decision to retain samples of the smallpox virus, the Ebola threat in Germany, the West Nile-like, mystery virus in New York and bizarre new supergerms like the killer staph bacteria outbreak and the flesh-eating strep bacteria that recently struck near Chicago.

Inspiring this cultural anxiety are real fears: the AIDS virus, germ warfare, biological terrorism, the U.S. decision to retain samples of the smallpox virus, the Ebola threat in Germany, the West Nile-like, mystery virus in New York and bizarre new supergerms like the killer staph bacteria outbreak and the flesh-eating strep bacteria that recently struck near Chicago.

"Epidemic! The World of Infectious Disease" screams the menacing poster for the current exhibition at New York's American Museum of Natural History -- a chilling multimedia demonstration of the global threat represented by virulent microbes.

"There was an earlier era when we really believed we would conquer bacteria and germs and viruses, " says University of Wisconsin historian Paul Boyer. "Now we see the natural enemy is far more ingenious than we realize -- we develop a defense against one form of a virus and it mutates into an even deadlier form. That's scary."

In the 1950s, people feared radiation, fallout and global thermonuclear war. In science fiction films, nuclear anxiety dramatically expressed itself as nightmarish visions of gigantic insects and monstrous crustaceans terrorizing the world. After the prehistoric Beast From 20,000 Fathoms (1953) awoke from its million year sleep by the underwater testing of atomic devices, the screen was overrun by reanimated-by-the-bomb behemoths and radioactive mutants -- the giant ants of Them (1954), the enormous octopus of It Came From Beneath the Sea (1955), the colossal lizard of Godzilla (1956), the stupendous spiders of Tarantula (1956) and the Cadillac-sized grasshoppers that lumber down Chicago's Michigan avenue in The Beginning of the End (1957).

In the 1950s, people feared radiation, fallout and global thermonuclear war. In science fiction films, nuclear anxiety dramatically expressed itself as nightmarish visions of gigantic insects and monstrous crustaceans terrorizing the world. After the prehistoric Beast From 20,000 Fathoms (1953) awoke from its million year sleep by the underwater testing of atomic devices, the screen was overrun by reanimated-by-the-bomb behemoths and radioactive mutants -- the giant ants of Them (1954), the enormous octopus of It Came From Beneath the Sea (1955), the colossal lizard of Godzilla (1956), the stupendous spiders of Tarantula (1956) and the Cadillac-sized grasshoppers that lumber down Chicago's Michigan avenue in The Beginning of the End (1957).

"Nuclear fear became a shaping cultural force," says historian Boyer, author of Fallout and By the Bomb's Early Light -- books about nuclear dread. Bomb tests, American/Soviet saber-rattling, wailing air raid sirens and duck-and-cover holocaust exercises generated a paranoid atmosphere that pervaded American culture beyond sci-fi b-movies.

Books, essays and prestigious films explored the medical, psychological, and ethical implications of nuclear weapons: Nevil Shute's novel On the Beach (1957) -- reverently adapted to the screen in 1959, Harvey Wheeler's Fail-Safe (1962) - a 1964 movie, Kurt Vonnegut Jr's Cat's Cradle (1963) and Stanley Kubrick's satiric Dr. Strangelove (1964). Television shows like The Outer Limits and Twilight Zone frequently featured nuclear paranoia themes.

Following the 1963 nuclear test ban treaty, atomic anxiety waned. Although the Three Mile Island accident, the Chernobyl disaster and Reagan's vast military buildup brought a cultural upsurge of nuclear jitters in the 80s reflected in movies such as The China Syndrome, WarGames and The Day After, the collapse of the Soviet Union significantly reduced fears of atomic annihilation. "By the mid-1990s, the nuclear threat had mutated from its classic form -- a nightmarish world-destroying holocaust -- into a series of still-menacing but less cosmic regional dangers and technical issues," says historian Boyer. "When the nuclear bomb shows up in current movies it's often as a gimmick or a special effect."

Following the 1963 nuclear test ban treaty, atomic anxiety waned. Although the Three Mile Island accident, the Chernobyl disaster and Reagan's vast military buildup brought a cultural upsurge of nuclear jitters in the 80s reflected in movies such as The China Syndrome, WarGames and The Day After, the collapse of the Soviet Union significantly reduced fears of atomic annihilation. "By the mid-1990s, the nuclear threat had mutated from its classic form -- a nightmarish world-destroying holocaust -- into a series of still-menacing but less cosmic regional dangers and technical issues," says historian Boyer. "When the nuclear bomb shows up in current movies it's often as a gimmick or a special effect."

During the era of bomb terror, ancient fears of disease lessened as science conquered one plague after another, including small pox and the childhood scourge polio. "In the 60s we thought we were advancing into a golden biomedical era, but that kind of confidence was foolhardy and arrogant," says Philip Kerr, author of The Second Angel, a thriller set in a dark future when a deadly micro-organism infects most of the population and an intelligent computer virus alters human evolution.

As fear of nuclear apocalypse abated, AIDS threatened another kind of apocalypse -- a biological one. While the mysterious AIDS plague spread world-wide, ghastly new microbial horrors came to light. Richard Preston's non-fiction The Hot Zone (1994) raised bone-chilling fears of bizarre, highly contagious new viruses like Ebola, Marburg, and Lassa. Focusing on the microbe's insidious and deadly power, Preston elaborated gruesome descriptions of virus-induced human body meltdowns. "From the point of view of the virus, we humans are an enormous pile of meat," says Preston. "Viruses don't care about us . . . that we're intelligent. A virus is like Jaws in a test tube."

As fear of nuclear apocalypse abated, AIDS threatened another kind of apocalypse -- a biological one. While the mysterious AIDS plague spread world-wide, ghastly new microbial horrors came to light. Richard Preston's non-fiction The Hot Zone (1994) raised bone-chilling fears of bizarre, highly contagious new viruses like Ebola, Marburg, and Lassa. Focusing on the microbe's insidious and deadly power, Preston elaborated gruesome descriptions of virus-induced human body meltdowns. "From the point of view of the virus, we humans are an enormous pile of meat," says Preston. "Viruses don't care about us . . . that we're intelligent. A virus is like Jaws in a test tube."

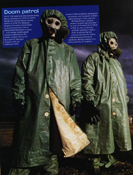

Following in the wake of the best-selling The Hot Zone came numerous horror-of-the-virus science books, including Leslie Garrett's The Coming Plague, Frank Ryan's Virus X, and Richard Rhodes' The Deadly Feasts -- all raised doubts about the survival of humanity and fueled the fear of biological vulnerability. In addition, the Gulf War brought us face-to-face with gas masks and the disturbing specter of germ warfare. Intransigent, antibiotic-resistant infections keep popping up, while diseases once linked with genes and environmental pollution -- like some cancers -- are now attributed to pathogens. "It's a Germ's World, After All" warns the cover of a recent issue of Natural History.

Repackaging mass fear as mass entertainment, The X-Files regularly delves into disturbing tales of dark biology involving a viral apocalypse brought on by the hideous black oil virus. This government/alien conspiracy to exterminate all life threads through the entire series (which began in 1994) as well as the X-Files feature film "Fight the Future." In addition, individual X-Files episodes center on other aggressive, invasive organisms: the worm-like, psychosis-inducing virus in "Ice," the deadly tropical microbe in "F.Emasculata," and the repulsive parasite in "Firewalker." With its unsettling mood of doomsday chic and flashlight-in-the-fog ambiguity, The X-Files focuses on the enemy within us.

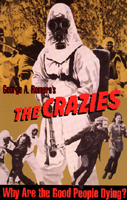

Inspired by The Hot Zone, Wolfgang Peterson's 1995 movie Outbreak takes a grimly realistic approach to contagion, showing human bodies crashing and bleeding out with the Ebola virus. Emphasizing the ease of communicability and the impossibility of knowing who's infected, Outbreak, The X-Files and other epidemic films like Robert Wise's The Andromeda Strain (1971), George Romero's The Crazies (1973), David Cronenberg's AIDS-prescient Shivers (1975), and Stephen King's The Stand (1994 TV adaptation) -- all reach a pitch of visceral terror and paranoid hysterics far beyond that of giant bug movies.

In Dean Koontz's current best-seller Seize the Night, the hero fights military scientists who have turned a pleasant town into a virus-infected police state after a biological experiment goes awry. Reflecting a post-Vietnam, post-Watergate cynicism, Seize the Night, The Andromeda Strain, The Crazies, The X-Files, Outbreak and other epidemic stories reveal dark suspicions toward scientists, misguided by megalomania and hubris. "Viruses that threaten to get out of control lead to a breakdown of confidence in modern medicine and in our mastery of the natural order," says historian Boyer.

In Dean Koontz's current best-seller Seize the Night, the hero fights military scientists who have turned a pleasant town into a virus-infected police state after a biological experiment goes awry. Reflecting a post-Vietnam, post-Watergate cynicism, Seize the Night, The Andromeda Strain, The Crazies, The X-Files, Outbreak and other epidemic stories reveal dark suspicions toward scientists, misguided by megalomania and hubris. "Viruses that threaten to get out of control lead to a breakdown of confidence in modern medicine and in our mastery of the natural order," says historian Boyer.

AIDS -- like no other disease -- engenders widepsread suspicion and mistrust of doctors, scientists and their corporate pharmaceutical sponsors. The slowness of the governmental response, the blame-the-victim scrape-goating by medical professionals, the vested interests of pharmaceutical companies as well as the legal dispute and chicanery associated with the discovery of HIV fuels the public's paranoia.

Medical paranoia infuses the novels of Dr. Robin Cook, king of the microbe-driven thriller with Invasion, Contagion, Toxic and his most recent Vector. Outbreak -- adapted into a TV-movie called "Robin Cook's Virus" -- turned on the deliberate spreading of the deadly Ebola virus by malevolent, HMO-hating doctors. "I've used medical paranoia to get the public's attention to deal with certain issues," says Cook. "Issues that deal with medical ethics or, in the case of Vector, the very real threat of biological terrorism."

Now front page news, bio-terrorism adds a ghastly dimension to plague paranoia. "It's the poor man's nuclear weapon," says historian Boyer. "You can whip it up in a bathtub and kill millions of people." In Cook's Vector, neo-nazi skinheads assault New York with weaponized anthrax. Even more terrifying, Richard Preston's novel The Cobra Event centers around a bio-terrorism attack with a doomsday virus created in a bioreactor. "Ebola is horrible enough," warns Preston. "But scientists are white-knuckled scared about even more terrifying viruses coming out of laboratories. My fear of nuclear weapons has been transferred into my fear of biological weapons."

Now front page news, bio-terrorism adds a ghastly dimension to plague paranoia. "It's the poor man's nuclear weapon," says historian Boyer. "You can whip it up in a bathtub and kill millions of people." In Cook's Vector, neo-nazi skinheads assault New York with weaponized anthrax. Even more terrifying, Richard Preston's novel The Cobra Event centers around a bio-terrorism attack with a doomsday virus created in a bioreactor. "Ebola is horrible enough," warns Preston. "But scientists are white-knuckled scared about even more terrifying viruses coming out of laboratories. My fear of nuclear weapons has been transferred into my fear of biological weapons."

With virus fear on the rise, even 50s-style mutated creatures -- caused by microbes rather than radiation -- are making a comeback. In the recent b-movie Virus an intelligent electronic virus infects a ship's computers and generates gigantic man/machine mutations. In Seize the Night, a retrovirus transforms people into grotesque monstrosities. In Parasite Eve -- a playstation game adapted from a best-selling Japanese novel, a resurrected, prehistoric organic force causes the cells of living things to mutate into a spider-woman, a giant worm, a three-headed dog, and a reanimated triceratops.

With virus fear on the rise, even 50s-style mutated creatures -- caused by microbes rather than radiation -- are making a comeback. In the recent b-movie Virus an intelligent electronic virus infects a ship's computers and generates gigantic man/machine mutations. In Seize the Night, a retrovirus transforms people into grotesque monstrosities. In Parasite Eve -- a playstation game adapted from a best-selling Japanese novel, a resurrected, prehistoric organic force causes the cells of living things to mutate into a spider-woman, a giant worm, a three-headed dog, and a reanimated triceratops.

Emerging from under the shadow of the mushroom cloud, we've become enveloped in a new darkness. "The single biggest threat to man's dominance on the planet is the virus," says Nobel Prize winning microbiologist Joshua Lederberg. Uniquely fearsome, the virus goes beyond nuclear fear to the heart of paranoia. "Virus fear is an ancient fear," says horror critic David Skal. "It's the fear of something invisible -- something insidious -- getting into our bodies, our bloodstream and controlling us, changing us, transforming us, or eating us from within." The virus not only provokes primeval fears of disease, dehumanization, vampirism and biblical vengeance but raises futuristic fears of human extinction. In many ways, the virus is the ultimate horror.

I