CULTURE SHOCK

WAITING FOR FELA IN LAGOS, NIGERIA (1983)

“To Many Westerners, Africa makes no sense at all, primarily because they apply Western values to a land that is not comparable with any on earth. ” -- David Lamb, The Africans

“Lagos is a city of superlatives. Estimates of its present population indicate that it may be the largest city in Africa, just ahead of Cairo. It is the world's most expensive city and it may also be one of the most criminal, the most dangerous to drive in, the most dirty, overcrowded and chaotic. Statistics cannot measure its aggressiveness, its endemic incompetence nor the corruption and arbitrariness of its haphazard bureaucracy. For maximum culture shock, Lagos is the place for white men to visit. ”

-- Martin Leighton Africa’s Richest Nightmare

I left the United States on January 22,1983, to spend three weeks in Lagos, Nigeria, West Africa. One suitcase contained my clothes; another suitcase contained 57 rolls of Super-8 movie film and 35mm slide film, three cameras, a small tape recorder, two microphones and assorted cables and batteries.

I hoped to make a short movie about the legendary African musician Fela Anikulapo Kuti in order to raise money for a larger project about the pop music scene in Lagos. At a minimum, I wanted to see Fela and the other musicians in Lagos: Sunny Ade, Commander Obey, Sonny Okossun, Chrissie Essian, and Bongos Ikwue among others. I wanted to learn about the scene and whether it was possible to make a movie in Lagos, the music capitol of Africa. I am white so I had a lot to learn.

I was accompanied by a Nigerian named Joe -- a student in the film & video department at Columbia College, Chicago, where I am a teacher. Joe offered to assist me in shooting the movie, to give me a free place to stay at his home and to provide transportation. Most exciting, he claimed to be a friend of Fela's and was very optimistic about the possibility of filming him, despite the fact that Fela had not returned my letters of inquiry.

African Rebel/Black President

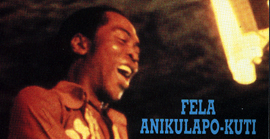

Fela Anikulapo Kuti is Africa’s best known and most fiery musician; he mixes radical politics and pop music as they have rarely been mixed before. Now in his 50s, the singer, saxophonist and keyboardist popularized his unique blend of Western funk and traditional African rhythms along with his own tribal religion. His name means “He who emanates greatness, who has control over death, and who cannot be killed by man.”

Fela Anikulapo Kuti is Africa’s best known and most fiery musician; he mixes radical politics and pop music as they have rarely been mixed before. Now in his 50s, the singer, saxophonist and keyboardist popularized his unique blend of Western funk and traditional African rhythms along with his own tribal religion. His name means “He who emanates greatness, who has control over death, and who cannot be killed by man.”

His mother Fumilayo was a pioneer in Nigeria’s struggle for independence: she led the fight for women’s suffrage and won. She begat a rebel. Fela’s music and life style are synonymous with protest and revolt.

A self-styled disciple of Kwame Nkrumah and his Pan-African socialist ideas, Fela has been waging a musical war with Nigerian authorities for more than 15 years. The police began harassing him in 1974 for smoking marijuana and housing runaways. Songs like the anti-military "Zombie" and the anti-capitalist "I.T.T. International Thief Thief" express Fela’s sarcastic criticism of African authorities and Western exploiters. With his driving Afro-Beat style, he fused the theatrical flash and funk of James Brown with African polyrhythms and the rhetoric of Malcolm X in the service of African Independence.

By the mid-70s, he had opened his own nightclub in Lagos which he called The Shrine. Proclaiming the Kalakuta (or rascal) Republic, Fela established a nearby commune. He maintained a harem of wives (polygamy is legal in Nigeria) known as the Queens, some of whom were dancers and singers with his band. Flaunting his image as a rebel by chain-smoking spliffs of marijuana from the stage of The Shrine, he launched into political and personal attacks on Nigerian authorities. Fela, the Black President, was idolized by the young and poor.

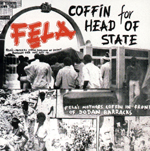

The government struck back in 1977. More than 1,000 soldiers laid siege to Fela’s compound for 15 hours. The rampaging soldiers raped some of the Queens and threw the singer’s mother from a window -- she later died from the injuries. Fela brought her coffin to the police station and put a photograph of this event on the cover of his his next album Coffin for Head of State.

The government struck back in 1977. More than 1,000 soldiers laid siege to Fela’s compound for 15 hours. The rampaging soldiers raped some of the Queens and threw the singer’s mother from a window -- she later died from the injuries. Fela brought her coffin to the police station and put a photograph of this event on the cover of his his next album Coffin for Head of State.

Declaring his mother a Yoruba spirit, he turned his nightclub into a literal shrine replete with an altar and all the religious trimmings. Attacking Christianity and Islam as parasitic colonial imports, he defended animism and the wisdom of African religious traditions. He changed the name of his band to Egypt 80, explaining that "the pyramids were built by Africans."

Declaring his mother a Yoruba spirit, he turned his nightclub into a literal shrine replete with an altar and all the religious trimmings. Attacking Christianity and Islam as parasitic colonial imports, he defended animism and the wisdom of African religious traditions. He changed the name of his band to Egypt 80, explaining that "the pyramids were built by Africans."

Mother Africa

For a year, Fela obsessed me. His music, politics (except for the sexism) and lifestyle combined romanticism, eroticism, marijuana smoking and ancient spirituality. But my year- long research had reached a dead end. After interviewing African music experts in Chicago and the Midwest, applying for grants, listening to his records and tallking with my friends Jo Ryan, Nina Sammons and Bruce Real. Jo and I drove to Ann Arbor and met Frank Fairfax who had been to Lagos and met Fela. Soft-spoken and kind, Frank said "The only way to understand Africa and Fela was to go to Africa and see Fela."

Suddenly, through Jo Ryan, I met Joe who made his offer to take me to Fela. I raised money, secured my first passport, visa, immunizations. Though I had other contacts in Africa, I felt very dependent on Joe. Just before we leave, he informs me that he’s a major in the military.

The flight to Nigeria takes 14 hours. We fly all night and arrive at day-break in Lagos. Military men meet us at the airport. Everyone salutes Joe and generally grovels before him. The group of military men move through the airport very quickly as I hurry to keep up with them. They rush past the authorities who check everything. But I'm stopped. Joe and his entourage seem to have forgotten me. I'm already panicing but, after a lengthy delay, I'm allowed through.

Stuck Outside of Lagos

We get into a military car. I assume we are going to Joe's house. This is the first of many wrong assumptions. The drive takes us through a major market with masses of people offering all imaginable goods. I'm amazed. Joe and his military friends are embarrassed by the sight and call it "a mess."

We arrive at the Durbar Hotel. I'm surprised that we're at a hotel. Joe says "The military is paying for it. My house isn't ready." The Hotel is not even in the city. It's like a prison. We are at some distant intersection of highways. Nearby are unfinished buildings that people have moved into anyway.

We arrive at the Durbar Hotel. I'm surprised that we're at a hotel. Joe says "The military is paying for it. My house isn't ready." The Hotel is not even in the city. It's like a prison. We are at some distant intersection of highways. Nearby are unfinished buildings that people have moved into anyway.

I start my first night in Mother Africa drinking with Joe’s friends at the hotel bar. Joe is from the Hausa tribe and speaks Hausa to his friends. They eye me like a sideshow attraction. Joe's friends all have decent jobs -- Nigeria Airways Executives or Building Contractors.

At dinner, Joe and his friends want me to eat chopped goat’s head but I beg off and fail a cultural bonding test. The outdoor restaurant/shack is illuminated by black light and a television. Nigeria’s current president Shehu Shagri gives a speech that all ignore.

We roar down the road at 120 miles per hour -- no speed limits, no traffic laws of any kind. But there are unpredictable roadblocks manned by young boys with big machine guns. They wave flashlights, signaling cars to stop. They check for armed robbers and non-Nigerians. The government has just expelled two million aliens, giving them two weeks to get out. The young soldiers look us over and check our papers.

We arrive at a small disco, the Phoenicia Club. The place is filled with African men. It’s impossible to talk because the music’s too loud -- no African music rather American funk: the Gap Band, Grace Jones, Prince. Colored lights flash in the darkness. It’s a sleazy place. I’m getting drunk, increasingly frustrated, and wondering what’s going to happen. One of my favorite songs plays - the Gap Band's "Early in the Morning" - so I dance clumsily. I’m floating out of my head.

By 3 am Joe and his friends, though married, have selected their women. Joe wants me to have one, but I refuse. As we leave I notice a tall and powerful looking man who stands above the whole tawdry scene. Joe knows him but doesn’t introduce me. He later becomes more important to me than Joe. We roar back to the Durbar Hotel, narrowly avoiding a dead cow in the road.

In the morning, there is no electricity and no hot water. I take a cold shower and wait for Joe. A military driver picks us up in a jeep. Joe’s car, like his house, is not ready. We intend to go to the National Theater Museum where one of my most important contacts Tunde Kuboye works. Tunde, who plays in a band called Extended Family, is married to one of Fela's nieces. I tried to call Tunde before we left the hotel, but the phone did not work.

Fire in the Street

Shortly after leaving, we are forced into the legendary Lagos traffic known as Go Slow -- a massive traffic jam of indescribable chaos. We inch across a bridge for three hours. Drivers continuously and uniquely honk, while recklessly attempting to squeeze into small breaks in the line of cars. Buses - looking like they’ve driven from the set of Road Warriors -- scrape cars and taxis even hit other cars, but no one stops. Cows and goats block the roads. Hawkers hold dead chickens by their throats and thrust them through open car windows. As we inch through Go Slow the sellers deal fake birth certificates, gold serving trays, wallets, key chains, water faucets, cassette players and videocassettes of E.T.

In the distance, I see a large building on fire. Smoke pours out of the upper windows. I learn later that this is the largest building in Africa, the forty story NET (Nigerian External Communications) Building, the pride of Nigeria. As we near the burning building, I see one fire truck and one hose. A man raises the hose so our jeep can drive under it.

In the distance, I see a large building on fire. Smoke pours out of the upper windows. I learn later that this is the largest building in Africa, the forty story NET (Nigerian External Communications) Building, the pride of Nigeria. As we near the burning building, I see one fire truck and one hose. A man raises the hose so our jeep can drive under it.

The next day horror stories of the NET fire fill the newspapers. A few weeks ago, there were reports of large scale fraud involving highly placed officials of the NET. The fire broke out on the very floor that housed the offices of the officials under investigation. Fire fighters complained about a lack of essential equipment. One newspaper said: "The fire should surprise no one: our present problem stems out of the incompetence of the people in charge of security in this country, people whose reasoning ability is less than zero."

Kalakuta

Finally, we arrive at the National Museum but my contact has already left. I'm upset. I suggest we go to see Fela. Joe agrees but first we stop at a military compound where Joe seems to show me off. The Colonel treats me like an important emissary from the United States. Embarrassed by Lagos, he says, "Lagos should be abandoned, left to rot itself to death." He wants me to see other parts of Nigeria and offers to pay for my transportation. I just want to see Fela. Fela’s house is brightly lit in the darkness. Outside, a man plays piano. Fela's music blasts out of large speakers. Several wildly made-up women -- presumably Queens -- hang out, talking. Joe knocks on the door of Fela’s white house. When a man answers, Joe says: "We want to see the President; tell him his old friend Major Joe is here." We return to the Durbar Hotel and drink with Joe's friends. The NET fire is a severe embarrassment to them. It seems to symbolize their frustration as a class. A former British colony, Nigeria experienced an oil boom in the 1970s creating a get-rich-quick mentality which led to the emergence of a generally corrupt elite far removed from the millions of poverty-ravaged peasantry who form the bulk of the country's population. So far, I’ve only taken still photos. I’m aware of drawing ugly attention when I raise my camera. Most Nigerians do not like to be photographed. My Chicago friend and Lagos visitor Marilyn Houlberg warned me about this. Some are embarrassed about Lagos and don't want its negative aspects revealed to the world. Others says it's pure business -- Nothing is free in Lagos; you have to pay for photos just like everything else. Enjoyment is Unlimited

Zombie Friend

Another horrific traffic jam the next day, but I finally connect with Tunde Kuboye at the National Museum. I am surprised to discover that I had seen him in the Phoenicia Club my first night in Lagos -- the tall, handsome man. He’s irritated that I’ve already seen Fela. He tells me that it’s important to be introduced by the right people. He says my conversation with Fela was influenced by the fact that I was with an upper class military man, a "Zombie." He implies that Fela can be approached. We make an appointment to meet on Friday night. He will take me to Fela’s house and then to the Shrine. Losing It

Fela stands, in red underwear, brushing his hair in a mirror for a long while. With his back turned to us, he says "I see you in the mirror, Major Joe." After the interminable brushing, Fela sits. Tunde whispers to him and gives him a bottle of wine. Fela then addresses me, "Mr. Dinello, do you have all that you need?" I stammer out a request to talk with him again about filming. He says, "Come back in a few days and we can talk." I find Tunde who advises me to take a room in Ikeja, near Fela, and pursue my objectives. For the first time I feel strong. Tunde and Joe leave. I stay until 4am, then I.D. helps me negotiate a taxi ride back to the hotel. At 6 am, I explain to Joe that -- despite our plane reservations -- I want to stay and pursue Fela. We part on good terms. He even gives me money. As we drive, he tells me that his assistant Ade will help me shoot in Lagos. We stop to pick up Tunde’s friends Shariff and Catherine. We all enter Fela’s house. He's sleeping. For 20 minutes, we watch him curled up in his chair. A picture of his mother watches over him. A Bob Marley documentary plays on the TV. Finally he wakes and greets us. I feel good being here with these new people. Arrested

I return to the Ikoyi neighborhood, in good spirits, to take photographs. As I walk I see a traffic policeman, wearing a bright orange uniform shirt, directing traffic. I want to take his picture, but I know he won’t like it if he sees me. Impulsively, I turn quickly and shoot him. He does see me and gets very angry. "You took my picture. I will arrest you. Why did you take my picture?" I say, "I’m a tourist. I liked your orange shirt." He doesn’t hear me. "You will go with me to the police station," he shouts. Confessing to Fela

Duro, Fela’s piano player, meets me at the door to Fela’s house. This is the first time I’ve visited alone. He takes me inside, but Fela’s easy chair is empty. Fela’s manager says, "He's taking a bath; it will be at least an hour. Will you wait?" No problem, I say, I’ll be right back.

There’s lots of people here -- Fela's employees and hangers-on. All of them want to talk. I decide to make a film about them. I return to Fela’s house again hoping to convince him to let me shoot his performance. He’s sleeping. I return to my hotel. The power is off again. By flashlight, I get my equipment ready to shoot that night. Lost in Lagos

When I leave my room, I discover the heavily padlocked gate. I stare dumbfounded at the chains and lock. The manager appears and opens the gate. How do I get back in? "Just yell when you come back, I'll open it," he says. I do not feel secure. Finally I expose some film of Lagos. I got lots of shots -- at a distance. We tried twice to walk in crowds and angered people. They saw me as a potential assasin looking for victims. The situation got out of control. We had to retreat to the car. We felt terrorized. Still, through all the hassle it felt good to shoot. Police Beat My Friend

Filming goes well the next day except for one incident. I ask Felix, a sculptor working at the Shrine, to show me where he lives so I can film him there. As I shoot him walking back to the Shrine, across what seems to be an apartment complex, two angry policemen stop us. "What are you doing with this camera? This is a police barracks. What pictures are you taking?" he screams. Lagos Jump

I get to the airport, but not without incident. My taxi driver gets into a fist-fight with a policeman after being accused of stopping in the wrong place. I patiently stare out the window, waiting for them to resolve their disagreement. The taxi-driver shoves the policeman down out and drives off.

We make another stop to see Joe’s brother who insists on putting on his just-purchased video Tora Tora Tora. Things get hazy -- it must be the palm wine. I have been warned off the stuff but can't resist trying a few cups -- The Palm-Wine Drinkard by Nigerian writer Amos Tutuola is one of my favorite books. Like the others, I fall into a dead sleep. We’re awakened as the Japanese bomb Pearl Harbor. The Africans think it's hilarious to be watching this movie with an American. I smile stupidly. As the bombs crash on TV, the power goes out.

The room is thrown into silence and darkness. Daily power outages occur all over Lagos lasting from a few minutes to hours. The power stops suddenly and then inexplicably returns. Government buildings, big businesses and rich people have alternative generators that sometimes come on, but most people just sit it out. We all leave. We go to Fela's house in Kalakuta Republic, located in a poor section of Lagos known as Ikeja.

"I understand the African man’s mind, this why I still remain in the struggle, and I will not relent . . . I know I am a great man, I know I have a big sense, I can play music, but I know my country is a stupid country . . . so I must be political" -- Fela speaking at the University of Lagos, 1981.

The man ushers us into the living room where Fela sits in a large easy chair. Is it really him? He stands to greet us wearing only purple bikini underwear, which is all he ever seems to wear. He’s very skinny and smokes a huge reefer shaped like a clarinet. I can’t believe it. To spend the day in such frustration and then, all of a sudden, to meet Fela is stunning. Fela greets Joe, warmly it seems. Joe introduces me. We small-talk briefly then I get down to business: my film plans.

Fela says it will cost $150,000 to film him. I ask why he didn’t reply to my letters with this information. He says he wanted to find out how determined I was. I tell him that I need to shoot some stuff in order to return to the states and raise money. He says he's giving me his lowest price: less than that would be advertising and he doesn’t need to advertise. I wish Joe would say something, but he's looking away.

Fela says it will cost $150,000 to film him. I ask why he didn’t reply to my letters with this information. He says he wanted to find out how determined I was. I tell him that I need to shoot some stuff in order to return to the states and raise money. He says he's giving me his lowest price: less than that would be advertising and he doesn’t need to advertise. I wish Joe would say something, but he's looking away.

Fela believes he’s popular in America and his legend will continue to grow. I ask him for an official letter stating his terms. He agrees and invites us all to see him perform at the Shrine in two days. I’m depressed at his refusal to be filmed but happy to have finally met him. Maybe the final word has not been spoken.

Urban Nightmare

Though brimming with intense competitive vitality, Lagos is the ultimate in urban nightmares: Everything -- power, transportation, waste disposal, the political situation, the police, the telephone system -- teeters on the edge of chaos. The privileged class is uneasy. Obsessed with becoming an industrial nation immediately, Nigerians are embarrassed by their failure to deal quickly with problems in development. They blame Nigerians who have no pride and no patriotism, who "go to America to be educated and stay there to drive a cab."

Shooting People

The next day, we make it to Sunny Ade’s nightclub -- the Ariya (Enjoyment is Unlimited). The popular Sunny Ade plays JuJu music - a strongly rhythmical and uplifting style of African music -- and sings about positive things. Unlike the rebel Fela, he’s beloved by the elite. I know Ade is out of country but hope to film somebody at the club. We talk to Sunny’s beautiful and cooperative wife Adeniji -- the club manager -- who says we can come back tonight, hear Kollington Ayinia -- another juju musician -- and possibly film. We plan to see both Kollington and Fela tonight. We return to the Durbar. Things seem hopeful.

The next day, we make it to Sunny Ade’s nightclub -- the Ariya (Enjoyment is Unlimited). The popular Sunny Ade plays JuJu music - a strongly rhythmical and uplifting style of African music -- and sings about positive things. Unlike the rebel Fela, he’s beloved by the elite. I know Ade is out of country but hope to film somebody at the club. We talk to Sunny’s beautiful and cooperative wife Adeniji -- the club manager -- who says we can come back tonight, hear Kollington Ayinia -- another juju musician -- and possibly film. We plan to see both Kollington and Fela tonight. We return to the Durbar. Things seem hopeful.

But the night ends in absurdity. We wait for Joe’s friends to give us a ride but they never show up. Telephoning them is impossible: the calls don’t go through or are too noisy to understand. We hang out by the gates of the Durbar staring off into the darkness. I'm very depressed. I try not to blame Joe, but I think it's his fault.

Tunde's evaluation of the Lagos music scene is discouraging: The bands suspect exploitation by anyone with a camera. The Lagos armed robber epidemic makes people fearful to go out at night. Plus, Fela is stuck way up in Ikeja considered among the most dangerous areas.

Tunde's evaluation of the Lagos music scene is discouraging: The bands suspect exploitation by anyone with a camera. The Lagos armed robber epidemic makes people fearful to go out at night. Plus, Fela is stuck way up in Ikeja considered among the most dangerous areas.

I’m bewildered by this place. The images are wonderful but I feel like I’m stealing them. My camera is like a gun and it puts me in an adversary relationship. I’d like to walk through the streets, shooting, but I can’t. I must be surreptitious. I haven’t been able to enjoy anything because I’m gripped by the desire to film. The gargantuan traffic jams suck out my energy. I told Tunde I was frustrated. He asked how long I’d been in Lagos. I said, "Four days." He laughed. "Four days of frustration is nothing; people live with it their entire life."

The food I brought -- candy bars, cashews, health drinks -- is running out. I've been obsessive about what I eat and drink. My great fear is getting sick. Joe wants to leave Lagos and pressures me to travel around Nigeria with him. How can we do this and get any filming done? I hate that jeep. I’m sick of sitting in gargantuan traffic jams. I’m tired of Joe and his friends. Today, at one of the military stops, I listened to a high-ranking military man arrange a whore for his building contractor friend. Things are continuously delayed. I am dying, waiting.

I attempt to reach other contacts today: a disc jockey at radio station FRC 2, the pop radio station. He’s supposed to be back soon but he does not return. I wait for the head of the Nigerian Arts Council, but he does not return. Of course we make several military stops. More waiting, more traffic jams. The city demands an unbelievable amount of patience, even for someone who grew up in Chicago. No one knows anything for sure. Nothing is definite. Phone calls get through if you are lucky; someone will be there if you are lucky. So far I have not been very lucky.

Nothing is accomplished at night. When the jeep leaves the hotel, I think we are going to hear some African music but we end up at the Gondola Club and at the Phoenicia club again. I did not realize what was happening as Joe and his friends spoke Hausa when they changed plans. Another wasted night. Joe talks about leaving Lagos for the trip up north.

The next day I meet, by accident, an African musician Bongoes Ikewu at The Durbar Hotel, of all places. He agrees to be filmed in a week. He is also pessimistic about the music scene. Except for Mrs Adeniji, people are not very enthusiastic about the Lagos music scene.

The next day I meet, by accident, an African musician Bongoes Ikewu at The Durbar Hotel, of all places. He agrees to be filmed in a week. He is also pessimistic about the music scene. Except for Mrs Adeniji, people are not very enthusiastic about the Lagos music scene.

Joe’s trip north is delayed. We spend four hours trying to track down another musician, Sonny Okossun. As usual, nothing is clear. He lives here but he’s out. He's on tour. He’s moved. No one really knows. I'm losing interest in everything but Fela. I don't want to take that trip north with Joe. But I’m afraid of being in Lagos by myself.

At night I wait for Joe to secure us a ride to meet Tunde and see Fela. I’m determined to walk if I have to. I’m very tense because we're supposed to leave for the north tomorrow. At dinner I discuss the prospects of Joe helping with the film when we return. As I feared, he will be very busy in Lagos when we return. He seems unable to help me. Luckily, we secure a car, make our appointment with Tunde and return to Fela’s house.

Finding It at The Shrine

We go to Fela’s Shrine. This is what I came to Africa to see. I feel resurrected. This is Africa. Everything else has been a shadow. I enter with Tunde and Fela’s business partner, I.D. Everyone greets them warmly. Joe follows behind. The Shrine is a huge, walled, but roofless concert hall. The walls are splashed with psychedelic patterns and colors. A Ghanian man sells reefer, political books and Fela albums. I buy some of everything. This Ghanian -- Krishna -- becomes a good friend.

We go to Fela’s Shrine. This is what I came to Africa to see. I feel resurrected. This is Africa. Everything else has been a shadow. I enter with Tunde and Fela’s business partner, I.D. Everyone greets them warmly. Joe follows behind. The Shrine is a huge, walled, but roofless concert hall. The walls are splashed with psychedelic patterns and colors. A Ghanian man sells reefer, political books and Fela albums. I buy some of everything. This Ghanian -- Krishna -- becomes a good friend.

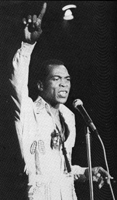

Egypt 80 starts playing at 10pm. After midnight, Fela enters. A path opens for him as people clap, cheer and shout greetings to the Black President. Tunde ushers Joe and myself to the very front of the stage. Fela’s band consists of two drummers, two guitarists, four percussionists, bass, keyboards, and a five piece horn section as well as four Queens in individual go-go booths. Fela comes to center stage and blows sax. I’m overwhelmed by the intensity of the performance. He never stops moving, singing, playing sax and keyboards, talking.

I’m hyped up and can’t sit still. I ask Joe to walk around with me and he says, "I can’t. I don't want to be recognized here." My body shakes, my heart explodes, I want to dance, to move around. I tell him that I need to walk around and ask "You won’t leave without me, will you?" Joe replies, "No . . . not unless you are missing." At first, this scares me. I’m the only white person here. I recognize how my relationship with Major Joe has been dominating and distorting my experience and the perceptions of others especially Fela. As I walk around the Shrine alone, everyone is friendly. It’s exhilarating, fun.

I’m hyped up and can’t sit still. I ask Joe to walk around with me and he says, "I can’t. I don't want to be recognized here." My body shakes, my heart explodes, I want to dance, to move around. I tell him that I need to walk around and ask "You won’t leave without me, will you?" Joe replies, "No . . . not unless you are missing." At first, this scares me. I’m the only white person here. I recognize how my relationship with Major Joe has been dominating and distorting my experience and the perceptions of others especially Fela. As I walk around the Shrine alone, everyone is friendly. It’s exhilarating, fun.

The scene surrounding Fela is startling, like the liberated zone of a new society. Most people interact with the performance, either dancing or responding directly to Fela’s lyrics. Clouds of reefer smoke hang sweetly in the air. Behind the stage is a huge sign that reads "Blackism is a force of the Mind." I realize that the only thing that matters to me is Fela. I need to stop flailing around and focus on him. I decide not to leave with Major Joe the next stay. I resolve to stay in Lagos on my own.

The scene surrounding Fela is startling, like the liberated zone of a new society. Most people interact with the performance, either dancing or responding directly to Fela’s lyrics. Clouds of reefer smoke hang sweetly in the air. Behind the stage is a huge sign that reads "Blackism is a force of the Mind." I realize that the only thing that matters to me is Fela. I need to stop flailing around and focus on him. I decide not to leave with Major Joe the next stay. I resolve to stay in Lagos on my own.

Hit the Road, Jack

I watch the lizards run around my window and then fall asleep. Later I get a sandwich in the hotel bar and talk with three young hotel workers. They love Fela; they hate the privileged class. The electricity fades in and out as they talk.

I watch the lizards run around my window and then fall asleep. Later I get a sandwich in the hotel bar and talk with three young hotel workers. They love Fela; they hate the privileged class. The electricity fades in and out as they talk.

The next day I move, by taxi, to a new hotel in Ikoyi, near Tunde’s house. I know how to negotiate taxi rides now -- it’s imperative to clarify the price before the ride, otherwise the driver gouges you. Everything must be negotiated; nothing is straight forward. The Ikoyi hotel is more lively, more colorful, even the phone seems clearer. I’m rejuvenated.

I walk around the area -- the loveliest I’ve seen in Lagos -- with its huge houses surrounded by lush gardens. I discreetly take pictures. I feel white and conspicuous. People watch me curiously. A young woman tells me it’s unusual for a white man to stroll around. Most whites -- businessmen -- just conduct their business, shuttling between hotel and office, without glancing sideways.

Two Ghanaians -- two of the millions recently thrown out of Nigeria -- ask me to take their picture. Very warm, they congratulate me for "setting foot on Mother Africa." As I walk further I smell garbage then see the rotting hulks of cars and trucks, the grass growing up over their hoods around a dilapidated building -- a police station.

Back in my room, I wait for contacts to call back. My emotions are close to the surface. I want to talk to people, make friendly contact, feel comfortable, be human. I wait. I want to talk with Tunde. The room feels like it’s getting smaller. The electricity goes out. I find candles. Sitting in the dark, I have a panic attack. I smoke reefer purchased from Krishna at the Shrine. Then Tunde calls. His call brings luck -- the power returns: Light. Air conditioner. Refrigerator. TV. What excitement! Tunde will pick me up to see Fela.

Back to Kalakuta

Tunde takes us to a upbeat jazz club -- Numero Uno -- to hear his band Extended Family with Tunde on bass and Shariff on clarinet. Tunde also acts as emcee, getting the audience enthused. The band plays classics like "Misty," "Take Five," and then break into the opening of Ray Charles "Hit the Road Jack" - one of my favorite songs. Tunde announces my presence over the PA ("A visitor from Chicago") and invites me on stage. People give me big applause so I jump onto the stage. Shedding embarrassment at my bad voice, I scream out the chorus of "Hit the Road Jack" into Tunde's mike. For the moment, my confusion and self-consciousness disappear inside the good feelings generated by Tunde and the supportive crowd.

Tunde is very positive and supportive of my trying to shoot in Lagos. He tells me to be strong and not give up my goals. The next day I negotiate terms with his assistant Ade. I’ll pay him $150 to act as my security for few days of shooting. He’ll arrange for the taxi which will be another $100. I'm ecstatic.

He walks me to the side of the road where two other policemen and some civilians hang out at a coke stand. The angry policeman yells to them: "This man took my picture." The other policemen are shocked. They question me. I drop the names of Joe and other military men I’ve met, as if this will frighten them. The two policemen do seem conciliatory, but the angry one pushes me toward a nearby taxi. The bystanders ignore us. He shoves me into the taxi. I consider jumping out the other side and running but believe the angry policeman would shoot me. The taxi driver, apparently trying to save me, puts the car into gear for a getaway but the policeman instantly jumps inside as it pulls away. He orders the taxi to the trash-laden police station.

As we walk past the rotted, rusted vehicles outside the station, another policeman approaches. "This man took my picture," says the original cop. This new guy goes up in flames, smoke pouring out of his eyes. He becomes instantaneously insane -- I am sure he could kill me easily. "Why did you take this man's picture?" he screams into my face. He displays a dimension of hostility I have never experienced. I start to stammer my tourist explanation, but it’s clear that he doesn't care. "You're going to spend some time in jail," he says. I believe him.

The insane man stays outside. Inside the cramped office, three policemen sit behind a long desk. An old fan rustles chaotic piles of papers. Opposite the desk, against the wall, sit some forlorn Nigerians. They are dusty, as if they'd sat there for months.

The offended policeman explains my offense. The three policemen question me, "Are you a journalist?" No. (I hope they don't look in my bag and see my journal.) "Are you a spy?" No, I'm a tourist. The officers at the desk don’t go crazy, but they keep challenging me. "Why would a tourist come to Lagos?" Of course, I don't mention my interest the politically controversial, anti-police Fela. I drop every military name I know, but all my phone numbers are back at the hotel. After an hour of interrogation, I feel the tide is turning in my favor. The captain says, "The point is that this man is mad at you and is swearing out a complaint."

"I will pull out the film and smash the camera," I say dramatically. "You don’t have to smash the camera, just take out the film," he replies calmly. With a flourish I pull out the film and hand it to the offended one. I repress the pain of losing over 30 pictures. The Captain says, "OK?" The offended one goes, "No problem." He smiles, I shake his hand. We walk out of the station together. I’m free.

Outside, the insane policeman looks at me. "Where are you going?" he says. The originally offended one replies, "They let him go." I wish he had said, "I dropped my complaint." The insane one demands that I go back into the police station. "You’re going to jail," he says. I go back inside with him.

The insane one and the three desk officers argue about me. The captain says, "He’s free to go." The crazy one says, "He’s not." Back and forth they go. I turn toward the door, I turn away. This goes on for a long time. It becomes a shouting match: Go/Stay/Go/Stay. In order to break out of this, I walk aggressively toward the insane one, toward the freedom door he’s blocking. He punches me in the chest. I fall back. None of the other officers moves. He shoves me down on the bench with the dusty Nigerians, who make room for me without looking up. I look at the Captain, but he turns and leaves the room. The insane one takes his place behind the desk and starts writing out papers.

"Are you a journalist?" No, I’m a tourist. (I am not really sure what I am or who I am. I told them my hotel. What if they search my room and find my tape recorder, camera, suitcase full of film and reefer? I have no money to bribe these people. I tremble at the thought of a Nigerian jail. No one knows where I am -- no one in Lagos, no one in the U.S.) I ask for water. They refuse. I consider making a run for it, but decide to wait.

The Captain returns and orders the insane one to come with him. The originally offended officer stands near me. I say, "You're going to help me aren’t you?" "No problem," he replies. When the insane one returns, he seems calmer. Somehow the situation has been reversed. The insane one gives the camera to the officer, who hands it back to me and says "Let’s go." When we get outside the gates, I say, "I’m lost." He says "I’ll take you to the hotel."

As we walk, he tells me he’s thinking of going abroad and getting a camera like mine. I explain the benefits of my camera and tell him to look through the viewfinder. He’s impressed with it.

As we walk, he tells me he’s thinking of going abroad and getting a camera like mine. I explain the benefits of my camera and tell him to look through the viewfinder. He’s impressed with it.

We sit at the coke stand where I was arrested. He buys me a warm coke. One of the officers says, "So now you are friends?" Lawrence, the previously offended policeman, hands this officer my exposed film and says, "Yes we are very good friends." I ask Lawrence how this is possible. He explains that Nigerians need to quarrel before they can become friends. He says, "If we hadn’t argued we never would have met." He offers to get me extra license plates if I need them. He tells me I can come back tomorrow and shoot his picture.

Lying down in my room, I’m chastened and less secure. I keep imagining the insane one, upset about losing face, putting his fist through my hotel door. I decide to go see Fela and check out the hotel near his place. I negotiate a taxi ride through the Lagos landscape, which looks stranger the longer I stay. Acres of garbage burning in fields, rusted hulks of cars, trucks and buses creating a wall of metal along the roadside.

Lying down in my room, I’m chastened and less secure. I keep imagining the insane one, upset about losing face, putting his fist through my hotel door. I decide to go see Fela and check out the hotel near his place. I negotiate a taxi ride through the Lagos landscape, which looks stranger the longer I stay. Acres of garbage burning in fields, rusted hulks of cars, trucks and buses creating a wall of metal along the roadside.

I walk across the dirt road to the Enuda Guest House. The manager welcomes me. I ask if I’ll be safe? "Yes Yes, no problem, we guarantee that 100%." Do the phones work? "Just the one in the office, but you can use it anytime," he assures me.

I walk across the dirt road to the Enuda Guest House. The manager welcomes me. I ask if I’ll be safe? "Yes Yes, no problem, we guarantee that 100%." Do the phones work? "Just the one in the office, but you can use it anytime," he assures me.

I return to Fela’s and wait there for a long time with many others. We watch The Jeffersons on TV. Queens come and go. All are colorfully dressed with intricately designed facial make up and hair molded and frozen into abstract sculptures. One of the Queens speaks to me, but I don’t understand her. Is it because I’m deaf in one ear? Then she says, "Don’t worry I’m not talking to you." I’m confused -- my usual state of mind.

I return to Fela’s and wait there for a long time with many others. We watch The Jeffersons on TV. Queens come and go. All are colorfully dressed with intricately designed facial make up and hair molded and frozen into abstract sculptures. One of the Queens speaks to me, but I don’t understand her. Is it because I’m deaf in one ear? Then she says, "Don’t worry I’m not talking to you." I’m confused -- my usual state of mind.

Finally the chair is prepared for Fela -- pillows adjusted, a pack of Marlboros and 6 joints placed on a nearby pedastal. He enters and greets me. I stand, but he’s actually looks past me to a woman behind. "Hi, sister," he says. I sit back down.

Soon my turn comes to speak to him. I tell him that I am moving next door and will be his neighbor. He invites me to visit often. I’m anxious to get the letters he promised to write concerning his filmmaking terms. He says I.D. will take care of that, no problem. Then I pour out my mistakes, my confusion, my frustration. I tell him that his performance inspired me to escape my military escorts. He reminds me of a priest even though he is, as usual, sitting in his underwear, smoking a joint. I want him to understand me. He invites me to tonight’s performance.

Everyone welcomes me when I arrive at the Enuda Guest House. They apologize that there's no power right then. The water pump is broken, so there’s no shower. I clean up with water from a bucket. Lagos is a tough city, the cost for this room is $120/night. After sleeping I go outside and visit some of the various shacks where people sell cokes, reefer and candy. Most people recognize me from the Shrine and give me warm welcomes. I feel very comfortable here. I’m not worried about getting lost since everyone knows where Fela lives.

Again, I visit Fela. I explain about the film I want to make about artists at the Shrine. He is friendly but again refuses my request to shoot his performance. I'm crushed. I keep thinking I can manipulate the situation. And I keep failing. But I don't learn very well. My white Western perceptions get undermined, but then reemerge providing me with more comforting illusions. Even after Fela shatters my illusion of filming him, I have other illusions. For example, I’m confident I know my way around the neighborhood, that I can easily get to the Shrine. Maybe during the day, but the night is different.

I walk into the darkness and get confused. I don’t really know where I’m going. Nothing looks the same at night. I return to Fela’s house. Fela’s manager I.D. finds three boys to take me to the Shrine -- a labyrinthine journey through a tunnel, behind houses, along sewers. Ten men chant strangely and do a violent dance. I remember a friend’'s comments about armed robbers in Lagos: if you are lucky they only rob and beat you.

We finally get to the Shrine. Upon arriving a crippled man attaches himself to me, claiming to have met me before. He is so insistent and pathetic that I buy him a ticket. I stop inside to talk with Krishna. I sit down, the cripple sits next to me. I feel exploited. I try talking to the man but I can’t understand him. I.D. sits next to me and we have an incoherent conversation. Everything passes in a haze.

I am not moved by Fela’s performance, I am annoyed with him. I feel small and uninvolved. I do not find any of the people I met earlier in the day. Whatever seemed fascinating this morning about this culture has now escaped me. The disappointment of not being permitted to film leaves me feeling weak, alone, defeated, obsessed with a megalomaniac. I hate the pathetic room at the Enuda guiest House. I want to leave.

I am not moved by Fela’s performance, I am annoyed with him. I feel small and uninvolved. I do not find any of the people I met earlier in the day. Whatever seemed fascinating this morning about this culture has now escaped me. The disappointment of not being permitted to film leaves me feeling weak, alone, defeated, obsessed with a megalomaniac. I hate the pathetic room at the Enuda guiest House. I want to leave.

I decide to move back to the previous hotel, in Ikoyi, just to take a fucking shower. I feel weak. I feel white. I fear arrest and hassle. After sleeping and showering at the Ikoyi, I feel better. I will do the taxi cab shoot tomorrow, with Tunde’s friend Ade, and then move back to the Shrine area and shoot there.

Shooting Lagos

Later in the day, I went to see Fela and met his piano player Duro who brings me to his room inside Fela’s house. We walk through a hallway of showers. His room is small, barely big enough for the mattress. In the next room, a chicken hops about madly. His room has various cartoons and posters that relate to Fela. We smoke reefer and talk. He is a native Nigerian and worships Fela. He left his parents house because they tried to force him to watch television. He believes that Nigerian television is the root of their problems: generating the ambition to be just like the West -- cosmetics, fashion, technology.

Duro criticizes his people for taking on technology before they fully understand it, for failing to Africanize the technology. "We are losing our identity to machines," he says. He cites the NET fire as the perfect symbol of their problem. Duro believes the U.S. will crumble and fall into the sea. He calls America a massive sin against humanity. He sees Fela as a religious cultural force that will lead Africa back to unity.

Duro criticizes his people for taking on technology before they fully understand it, for failing to Africanize the technology. "We are losing our identity to machines," he says. He cites the NET fire as the perfect symbol of their problem. Duro believes the U.S. will crumble and fall into the sea. He calls America a massive sin against humanity. He sees Fela as a religious cultural force that will lead Africa back to unity.

Later tonight, Duro and I go to the National Museum to hear Tunde Kuboye’s band Extended Family. I speak briefly with Tunde to thank him and say good bye. Ade takes me aside and says to be careful of Fela’s people -- Fela only need give the word and they will kill me. You can’t mean Duro, I say. "Especially him," replies Ade. This is a bit unnerving but my experience with Duro has been all positive. We went home together.

They go crazy on Felix, slapping him around. He gets down on his hands and knees. I shake in fear, especially after they mention going to the police station. Yet, they ignore me and focus anger on Felix. I feel ugly since I am responsible for putting him in this situation for the sake of my lousy footage. He shrugs off the incident as typical and ordinary. I am ready to leave. Felix convinces me to return to the Shrine. Everyone there is very friendly. I interview Krishna as well as Bola, the man who designs Fela’s clothes. He gives me a shirt and a sculpture (a raised black fist) as going away presents.

Three months later I receive a letter from Krishna: The Nigerian Mobile Police force raided us on the night after you left. My wooden counter -- was broken and money was stolen along with my big cassette player that I used to play Fela music for my customers.

Of course my flight is delayed. I am hungry but do not want to eat meat on a stick. The loudspeaker calls out in a distorted, incomprehensible garble. In between, the same two songs play over and over. I am disappointed not to have filmed Fela, himself but I am very happy about what I did shoot and what I experienced in mother Africa.

Four months later Fela was arrested and sentenced to five years in jail. Amnesty International declared him a political prisoner. As a result of this trip, I was hired to make a a music video about Fela to publicize his arrest and his new song Army Arrangement. Immensely gratifying, the video brought a sense of closure to my African odyssey. Shown on MTV and elsewhere, it helped focus attention on the plight of this rebellious artist.

Fela was released after serving almost 2 years of his sentence. He toured the U.S. twice -- in 1986 and 1989. He died of AIDS in 1997.

I